Electrification and Solar

In breaking down how a North American household uses energy, there's a few key categories:

- Heating (space, water, cooking)

- Cooling (air conditioning, refrigeration)

- Everything else (lighting, electronics, etc.)

Heating

No surprise: heating dominates energy use in Canadian homes.

Traditionally, you can get heat in a few ways: either you burn some type of fossil fuel (natural gas is usually the cheapest option if it's available, since you can get it piped directly into your house) or you take electricity and use it to heat up an resistive material. The cost and availability of these options varies wildly depending on your jurisdiction.

The per-unit cost doesn't really matter all that much for something like a stove (which you use relatively rarely), somewhat matters for a water heater (where you are trying to keep a constant volume of water at a particular temperature), and matters a lot for heating a relatively large area in a place that gets cold.

Ontario has relatively inexpensive electricity, although our provincial neighbor, Québec, is cheaper still thanks to its abundant hydro-power. But even in these cases, this type of heating is pretty expensive: per unit of heat, natural gas (if you can get it) is almost always going to be way cheaper. It's much cheaper to burn something at the point of use than to generate electricity, transmit it, then make a resistive element hot.

However, there is now a third option! Enter heat pumps. Instead of using electric current directly to heat up an element, heat pumps extract heat from the air. Through a refrigerant cycle, they efficiently extract heat from the air outside and pump it inside. Heat pumps can move more total heat than the power required to operate them, so they are several times more efficient than electric resistance heating.

A crude way of measuring how much you use for space heating is just to compare your energy use in a shoulder season (spring or fall) to a winter month. To illustrate, here are the raw numbers for a couple months in the year before we embarked on this project:

While some small percentage of the above increase month over month has to do with lightning, the vast majority of extra electricity and gas use was due to indoor heating requirements. In addition to cranking up the gas furnace in the winter, we used an electric space heater to heat our bedroom at night so I could turn down the thermostat a few extra degrees.

Cooling

Ontario summers get somewhat hot and humid. As such, air conditioning (AC) is really nice to have. The two options for AC are both electric: a heat pump or a traditional air conditioner (which is less efficient). In either case, it's a smaller portion of your energy use. For example here's our comparative usage in the summer (before we got the heat pump) versus the previously measured shoulder month:

Roughly 130 kWh (or 4.5ish kWh per day), equalling an extra $20 on our electricity bill.

Everything else

Lighting, computers, vacuum cleaners, etc., etc. These things are essential to our quality of life, but in terms of actual energy use they're (usually) small potatoes. For brevity, I've left them out of the analysis.

Auditing our use

Before embarking on any of these projects, we got an energy audit from a local company called Green Venture. This was a prerequisite for the various loans and incentives we got from the government, but it would be something I'd recommend in any case to avoid making expensive upgrades that don't make a big difference. The auditor's findings and recommendations were pretty key to our decision making process.

The report gave an approximate number for the heating load of our house (giving us a baseline from which to improve) as well as:

- Some simple suggestions on how to reduce energy use through insulation (always the first thing you should do)

- A general recommendation to explore replacing our gas furnace with a heat pump and install a solar installation (dependent on cost and desire)

We wound up doing all of it!

Technologies deployed

Heat pump

We got a 3 Ton Fujitsu coldweather model (to be precise an AMUG36LMAS), backed by a 10kW electric resistance heat strip. Here's what it looks like:

There are different models of heat pump that you can buy based on your needs. Unlike gas furnaces (which are typically way over sized and will cycle on and off many times over the course of an hour), a heat pump you typically want to run all the time – cycling continuously is somewhat inefficient. We went with a 3 ton based on the aforementioned energy audit and me poring over manuals and specifications, and comparing previous runtimes of the nest thermostat. The resistance backup was there "just in case" I was wrong and the system wasn't capable of keeping up during a particularly cold day.

The good:

- It keeps the house warm in the winter, including on very cold days. We installed electric resistance backup but based on our electricity load I doubt it was used much if at all. More on this in the energy section.

- It acts as a central air conditioner, something we didn't have previously (we used a bunch of window units, which were a pain to install every season).

The less good:

- It's more expensive than comparable models like a Moovair (which my installer originally suggested). You pay for the brand name.

- The “smart” thermostat provided by Fujitsu feels like a bit of a step down from the Nest that we had previously. The app is unreliable and clunky to use, and I'm honestly wondering why I even bothered installing it over the default (not wifi enabled) controller that comes with the unit. You can theoretically connect a heat pump like this to a smart thermostat using an adapter, but much of what I've read online says you lose a fair bit of efficiency that way since there's no standard protocol for controlling an inverter-based technology, and the Nest winds up controlling the heat pump like a gas furnace (basically constantly telling it to turn off and on, rather than modulate its output).

I expect that technology here will continue to evolve over the next few years and I'd generally expect installation costs to go down and functionality and ergonomics to improve. If you're considering installing a heat pump, definitely shop around: I got wildly different quotes from the installers I talked to. My feeling is that under normal circumstances you shouldn't be paying more than $20k for a system install (and probably considerably less than that), even for a “fancy” Japanese model like what I got. The folks on Reddit's r/heatpumps were pretty helpful when I was shopping between quotes.

Solar

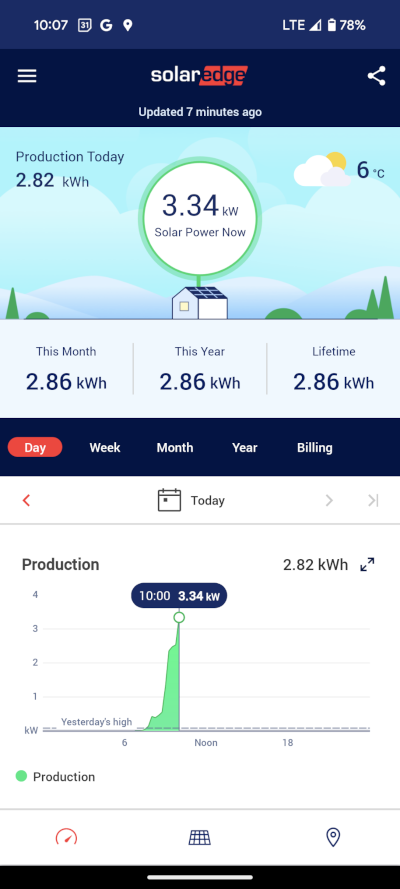

We initially weren't planning to go in this direction (I felt it was too complicated/expensive) but we got a pretty compelling sales pitch from a local company and decided to go for it. I don't want to go into exact figures about what it cost, but it was within the ballpark of the ~$20k that reliable sources usually give for a 6 kW system with a 5 kW inverter.

Honestly, it was pretty turn-key. I believe the system required a 200 amp panel, but we already got one for the heat pump. The company we went with took care of all the paperwork. A day or two of installation later, we were up and running.

Stove, dryer, hot water

Our plan being to get off natural gas altogether, there were some smaller appliances to take care of: hot water, stove, and dryer.

For hot water, we went with a boring old conventional electric heater, on account of us being a relatively small household that doesn't have high usage. A heat pump water heater was quoted as being several thousand more expensive, and it didn't seem worth the cost: it would probably take decades to recover the extra money.

We also replaced our old gas stove with a new induction range. Induction stoves are cool! We were a little worried about what the experience cooking with them would be, but so far it's been great. It has the same "turn the knob, get heat" behaviour we enjoyed from a gas stove, without the particulate emissions. It also boils water super fast!

We still have a gas drier that we haven't yet swapped out. 😭